In recognition of International Women’s Day on March 8 and U.S. National Agriculture Day on March 22, the U.S. Soy industry showcases two U.S. women farmers who grow food-grade soybeans.

In my role as executive director of The Soyfoods Council and a longtime advocate of sustainable U.S Soy, I recently spoke with Maryland farmer Jennie Schmidt and Wisconsin farmer Nancy Kavazanjian, who both discussed their long-standing commitment to producing high-quality, sustainable soybeans to help nourish the world. The two growers produce soybeans for livestock feed as well as food-grade soybeans for human consumption.

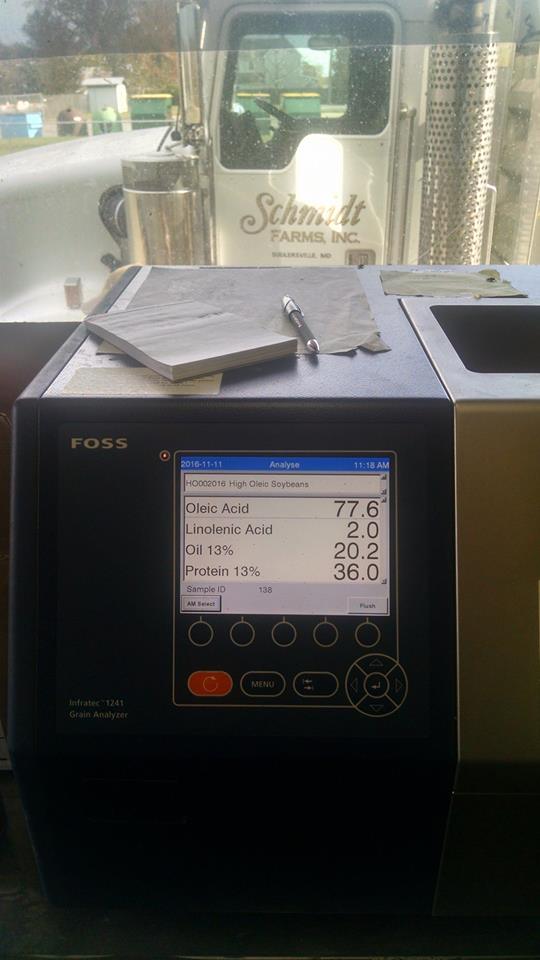

Jennie Schmidt, MS, RD is a Registered Dietitian and full-time farmer who formerly operated a vineyard management company. She and her husband Hans are part of the third generation leading Schmidt Farms in Sudlersville, Maryland, on the state’s eastern shore. The family has a long history of practicing sustainability and conservation.

Jennie Schmidt, MS, RD is a Registered Dietitian and full-time farmer who formerly operated a vineyard management company. She and her husband Hans are part of the third generation leading Schmidt Farms in Sudlersville, Maryland, on the state’s eastern shore. The family has a long history of practicing sustainability and conservation.

Today, Jennie Schmidt farms about 2,000 acres full-time on the diversified family farm with her brother-in-law Alan, while her husband serves as Maryland’s Assistant Secretary of Agriculture for resource conservation. Hans Schmidt was appointed to the position by the state’s governor in 2015. Schmidt Farms plants 800-900 acres of three different types of soybeans—commodity beans, high-oleic soybeans, and tofu soybeans. In addition, they grow wine grapes, corn, canning tomatoes, and green beans.

Nancy Kavazanjian has been farming sustainably for 42 years in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, with her husband Charles Hammer, who has an established history of agricultural innovation. On their 2,000-acre family farm in Dodge County in the southern part of the state, they emphasize preserving soil and managing resources sustainably. Kavazanjian notes that they are currently utilizing innovations such as prairie strips, which reduce soil erosion and provide wildlife habitat; controlled traffic farming (CTF) that restricts heavy machinery wheels to the smallest area possible to improve soil structure; drones; working with moisture probes in the field; and precision mapping for data collection.

Nancy Kavazanjian has been farming sustainably for 42 years in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, with her husband Charles Hammer, who has an established history of agricultural innovation. On their 2,000-acre family farm in Dodge County in the southern part of the state, they emphasize preserving soil and managing resources sustainably. Kavazanjian notes that they are currently utilizing innovations such as prairie strips, which reduce soil erosion and provide wildlife habitat; controlled traffic farming (CTF) that restricts heavy machinery wheels to the smallest area possible to improve soil structure; drones; working with moisture probes in the field; and precision mapping for data collection.

Kavazanjian and her husband grow corn, soybeans and small grains usually winter wheat or spring barley. On average, they plant 700-900 total acres of soybeans including identity-preserved (IP) and commodity soybeans. For the past 30 years, to meet consumer demands, they have grown value-added, IP soybeans that are isolated from commodity soybeans and are tracked through the food chain. The food soybeans they grow now are primarily a tofu variety — high-protein, clear hilum soybeans. Commodity soybeans are either exported whole or processed made into vegetable oil and livestock feed.

Demonstrating the Sustainability Commitment

Long before the U.S. Soy Sustainability Assurance Protocol (SSAP) was launched in 2014, sustainability was an important consideration at Kavazanjian’s family farm. “Sustainability has been important to us right from the start, but the way we put that into practice has evolved,” she explains. “Our motto, which we first adopted in 1980, is Our soil, our strength. That means we make sure our soils are the best they can possibly be. The way we achieve this includes everything from building organic matter and avoiding compaction to following good crop rotation, adding manure, using cover crops and adopting new technologies of precision agriculture.”

Kavazanjian adds, “We were early adopters of no-till, and strip-tilling when required, with control areas, pollinator habitats, precision farming for weed control and fertility as needed—and only when needed. Today we implement data collection and field mapping, to identify opportunities where we can farm our top acreage to the best of our abilities while looking for other ways to improve our problem areas.”

At Schmidt Farms, Jennie Schmidt holds a similar perspective. “We have a long history of sustainability and conservationism. We have a copy of an old Farm Journal from 1965 with an article featuring my father-in-law and our farm’s early adoption of cover crops and no-till agriculture. He and his brother were willing to try conservation, be progressive and were involved in ag leadership.”

She continues, “Sustainability is part of what we do. Take no-till: In the last 25 or 30 years, the majority of Maryland farmers have adopted it, and cover crops are increasing. We keep the nutrients in the ground over the winter. At our farm we also are Certified Agricultural Conservation Stewards, a sustainability certification offered by that state of Maryland.” [1]

Taking Pride in the Reach of High-Quality U.S. Soy

High oleic soybean oil, according to consensus in the U.S., has an oleic level of 70% to 75% or more and a high level of monounsaturated oleic fatty acids, compared to commodity soybeans that have a 22% to 25% oleic content. [2]

High oleic soybean oil, according to consensus in the U.S., has an oleic level of 70% to 75% or more and a high level of monounsaturated oleic fatty acids, compared to commodity soybeans that have a 22% to 25% oleic content. [2]

“We grow high oleic soybeans,” Schmidt says. “In food manufacturing, high oleic soybean oil replaced partially hydrogenated soybean oil after consumers moved away from trans fats that aren’t heart-healthy.” High oleic soybeans also enjoy a positive sustainability story at the farm level, thanks in part to the SSAP. [3]

Schmidt says of the three types of soybeans they grow, the commodity beans are supplied to a poultry company headquartered in Maryland. “Our high-oleic beans also go to them,” she adds. “They use the soybean oil, with its healthy amounts of monounsaturated fat, on the food manufacturing side. The soy protein ends up in chicken feed.” Tofu soybeans grown at Schmidt Farms are sold to Asian food processors.

“I know our beans are used internationally because I’ve traveled with USSEC to Japan,” Kavazanjian says. “During my trip, I was able to meet with a company that we sell our beans to; they then send those beans primarily to Kobe. Tofu is also a big product in the Asian market.

“I know our beans are used internationally because I’ve traveled with USSEC to Japan,” Kavazanjian says. “During my trip, I was able to meet with a company that we sell our beans to; they then send those beans primarily to Kobe. Tofu is also a big product in the Asian market.

“And when people in the U.S. want to know where our soybeans go, I tell them, ‘Look at the vegetable oil you use all the time.’”

Strengthening the Soy Nutrition Connection

As a registered dietitian as well as a farmer, Schmidt enjoys working on the food side of the crops they grow. “It keeps my finger in the pie of nutrition. I do a lot of speaking to dietetic groups, and it’s good that I can stand up in front of my peers and speak to the farming side of food. When I speak to consumers, I let them know I’m a mom and we eat the food we grow. If I wasn’t comfortable with what I’m doing on the farm, I wouldn’t be serving it to my kids.

“I’m still using my nutrition degree. The science is the same; it’s just a different biological application. I understand the human science of biology and now apply it to plants and soil. Humans are not compliant with their diet recommendations, but plants and soils are. I’m still a dietician, I’m just a dietitian for plants and soil.”

In providing quality nutrition for people around the world, the work of U.S. soybean farmers like Kavazanjian and Schmidt helps advance the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), including Goal 2/Zero Hunger. That goal includes ending hunger, achieving food security and improved nutrition, and promoting sustainable agriculture by 2030. [4] From field to fork, U.S. Soy is committed to being part of the sustainability solution. [5]

This article was funded by the United Soybean Board.

- Retrieved from “https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/md/programs/financial/csp/”.

- USSEC, “U.S. High Oleic Soybeans & High Oleic Soybean Oil Sourcing Guide for International Customers.” Second edition, pg. 34, September 2021.

- USSEC, “U.S. High Oleic Soybeans & High Oleic Soybean Oil Sourcing Guide for International Customers.” Second edition, pg. 14, September 2021.

- Retrieved from “https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2016/Overview”.

- Retrieved from “https://ussoy.org/u-s-soy-the-sustainability-solution”.