How important is the Panama Canal to U.S. Soy?

The U.S. is an agricultural surplus country dependent on exports. The Inland Mississippi River System plays a major role in transporting commodities, especially soybeans and corn. Approximately 60% of all grain and soybeans inspected is exported through the Center Gulf, which consists of the U.S. Customs Districts of New Orleans, Louisiana and Mobile, Alabama. An additional 30% of all grain and soybeans inspected is exported through the Pacific Northwest (PNW), which consists of U.S. Customs Districts of Colombia-Snake, Oregon and Seattle, Washington. In 2018, approximately 127.9 million metric tons (MMT) or 4.7 billion bushels was exported, with over 76.2 MMT (2.8 billion bushels) exported through the Center Gulf. Of the 2.8 billion bushels (76.2 million metric tons), approximately 29.9 MMT (1.1 billion bushels) traverse the Panama Canal or approximately 40% of Center Gulf exports. Because not all of the 29.9 MMT originates in the U.S., the percent of Center Gulf exports that traverse the Panama Canal is closer to 35% or one out of every five bushels exported by the U.S.

The Panama Canal Authority announced a freshwater surcharge to be implemented February 15 without an end date. The canal is adding a $10,000 charge per transit and a second variable fee based on the water level of Gatun Lake when a vessel moves through the canal. It also added new limits on the daily reservation slots available to ships, along with other measures meant to limit the number of vessels moving through the facility each day.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the head of the Panama Canal expects seasonal restrictions on shipping, including new “freshwater surcharges,” to continue for several years until canal administrators find a long-term solution to droughts that have hit operations at the trading hub.

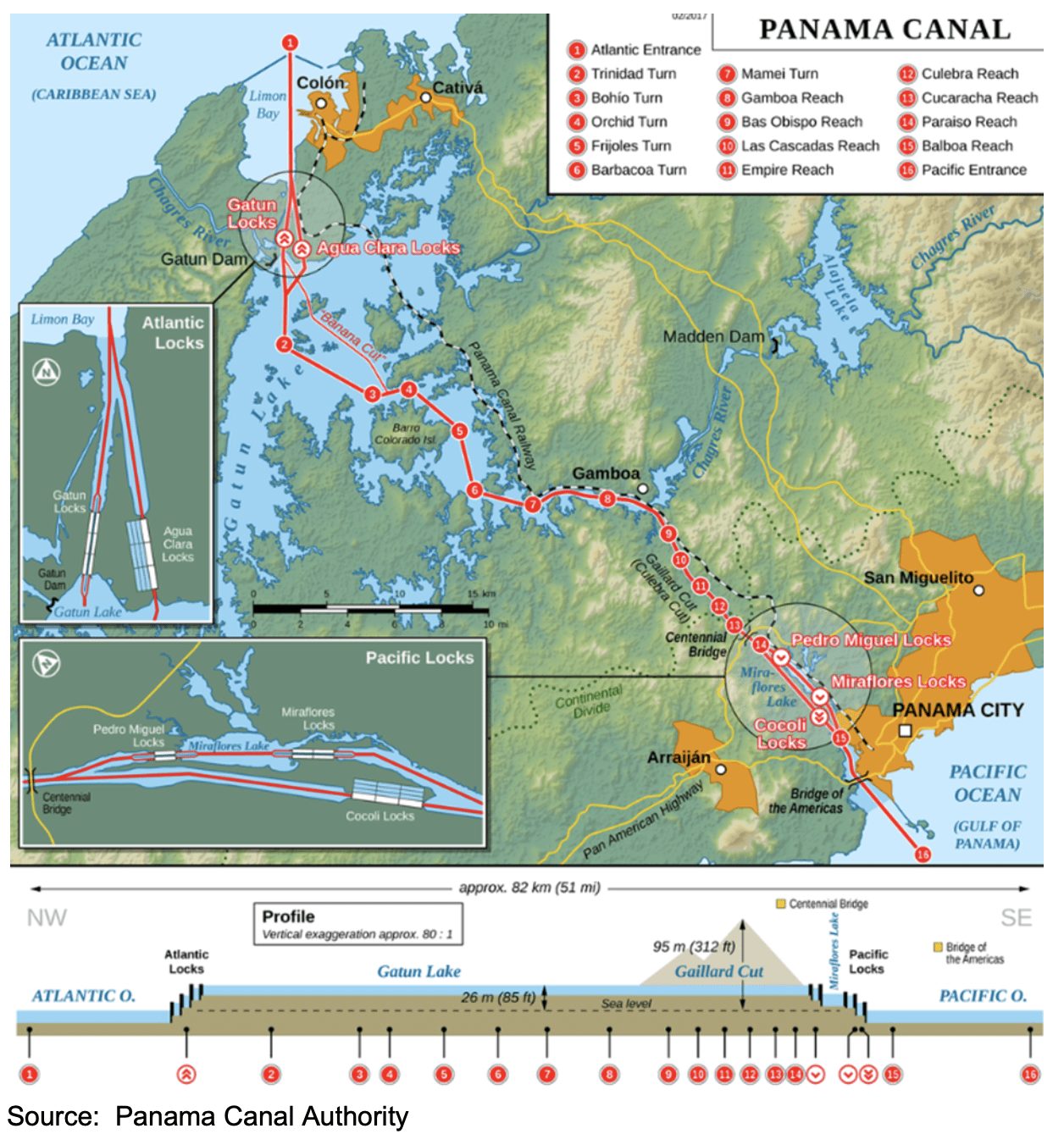

Canal Administrator Ricaurte Vásquez said authorities are considering pumping water from elsewhere in the country or building a dam that would store more water at Gatun Lake, which provides water to help ships pass through the locks between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. One would pull in water through a pipeline from a lake with higher water levels about 100 miles from the canal, a project that would cost more than $1 billion, said Vasquez. The second would be to build a dam to enable the canal authority to store more water and regulate the flow, a plan that would carry a roughly $2 billion price tag. Either project could take up to three years to complete.

What would a higher tariff at the Panama Canal mean to U.S. farmers? For European export destinations, the Center Gulf and East Coast is the obvious port choice and the Panama Canal is not in play. For Asian export destinations, a Western Corn Belt farmer has the export options of shipping the grain and soybeans to the Mississippi River to be barged out of the Center Gulf or railed to the PNW. The barge market is highly competitive, while the railroads have greater pricing power. For this reason, the grain and soybean prices at the Center Gulf, Brazil ports and Argentina ports compete and the PNW price is the other ports plus ocean freight spread. Since the Panama Canal situation impacts ocean freight price, all U.S. farmers are impacted by the Panama Canal tariff rate.

A Panamax vessel can load approximately 2.1 million bushels of soybeans or 57,000 metric tons. The extra landed cost per bushel to Asia will be approximately a half a cent higher. Ocean freight rates are at a nine-month low and will more than offset any increase in Panama Canal fees in the short-term.

The following is general information concerning common Panama Canal questions. The canal handled 13,785 vessel transits in its fiscal year ending September 30, 2019, most of them large oceangoing ships in international trade, and collected $2.59 billion in tolls, according to the Panama Canal Authority.

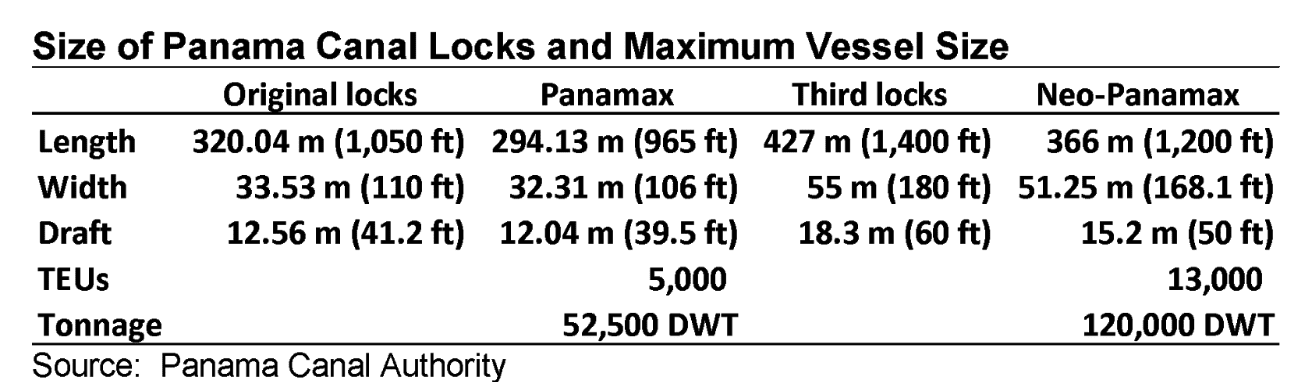

A Panamax vessel is the largest vessel that can traverse the old locks and a Neopanamax vessel is the largest vessel that can traverse the new locks. Note that there is no classification for a Neopanamax vessel in the following table. Approximately 30 vessels were built by grain merchants to take advantage of the new locks and can be loaded to 97,000 metric tons. With current ocean freight market conditions, incentive for building new bulk grain vessels is limited. The result is confusing terminology. Small Capesize, Large Panamax, Post Panamax and Neopanamax can be the same vessel. The new locks have increased the worth of Small Capesize vessels that can transverse the new locks.

The vessel size is designed to meet the needs of the port. The Handysize, Handymax, and Supramax vessels primarily service ports that either cannot handle larger vessels or handle the volume of the commodity. A common destination would be Caribbean and Central American markets that are unable to handle Panamax vessels.